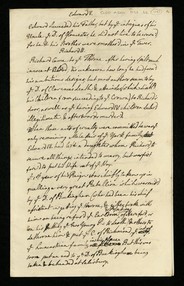

By this time, Shakespeare’s name had begun to appear in accounts of Richard’s life; as young Albert Edward notes (in lines scratched out at the bottom of this page, but reiterated overleaf), both Thomas More and Shakespeare ‘served under the Tudors, who would be inclined to blacken his character, [so] their account is perhaps not to be credited.’

Image: A handwritten page in an exercise book, with notes in copperplate handwriting, some ink blots, and several lines scratched out at the bottom of the page. It reads: ‘Richard III. 1483. Richard soon heard rumours of conspiracies to meet which he caused a report to be spread that his nephews were dead. The general belief was that Tyrrel had murdered them in the Tower. Unsuccessful rising in the West of England of the partisans of Henry, Earl of Richmond. He had crossed over from Britanny, & was prevented by storms from landing. Henry Earl of Richmond landed a second time, at Milford. He marched through Wales, & fought the Battle of Bosworth in Leicestershire, in which Richard’s army was defeated, & he was killed.’ The crossed-out lines read: ‘Shakespeare & Sir T. More hand down that Richard was hunchbacked & a deformed character. Their accounts may not be true, as they were staunch adherents of the Tudors, it is said he had a withered arm but as he was very brave in battle, it is held to be doubtful whether it is true.’

A hundred years after George III made his notes on Richard III, his great-grandson received a slightly more nuanced lesson on Plantagenet history.