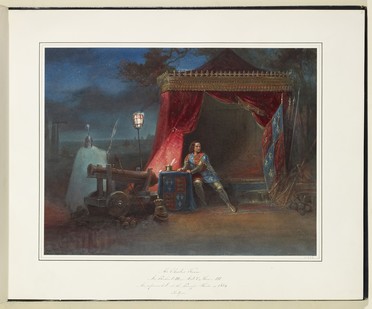

Richard III was condemned by the historians Sir Thomas More and Raphael Holinshed, but it was through Shakespeare’s eponymous play, revived and much performed from the eighteenth century onwards, that he became established as the power-hungry murderer who endures in the popular imagination.

Successive generations of royals, too, grew up with the Shakespearean image of Richard III – a narrative that continued to evolve into the Victorian era and beyond.

On 27 January 1838, after seeing Richard III at the theatre, Queen Victoria reported a discussion with her first Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, that blurred together the historical figure and Shakespeare’s character: 'I observed that Richard was a very bad man; Lord Melbourne also thinks he was a horrid man; he believes him to have been deformed (which some people deny).'

The question of Richard’s disability (which, the queen notes, ‘some people deny’) was only settled in 2012, when his skeleton was exhumed in a Leicester car park and found to display curvature of the spine.