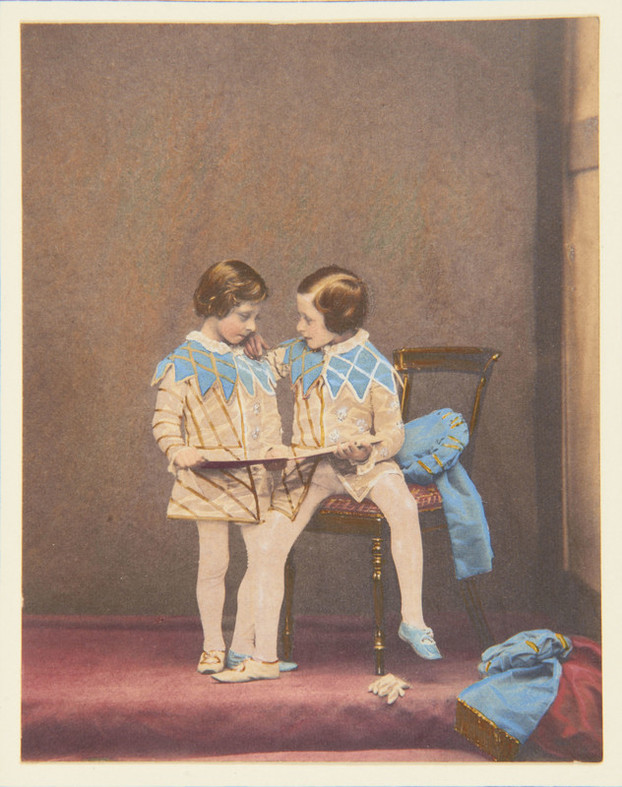

The Princes in the Tower (featuring two of Queen Victoria's grandchildren) was one of a series of tableaux staged in 1888 to celebrate the thirtieth birthday of Prince Henry of Battenberg.

The choice shows the royal family’s continued fascination with this period of history and Shakespeare’s depiction of it. In this case, the story was a vehicle for a moral about the innocence of children - as well as an oblique reference to Richard's villainy. As Queen Victoria herself had remarked in her diary fifty years earlier: 'Richard was a very bad man [...] there is no doubt that he murdered those two young Princes'.

With this tableau vivant, the royal family came full circle: from perpetuating the Shakespearean version of Richard to acting it out themselves.

![A print of two men shaking hands. On the left is the Prince of Wales; he wears fashionable 1780s costume, including a tailcoat, tight breeches, knee-high boots, a prominent cravat and a bicorn hat. He holds a riding crop in one hand, tucked behind his back. On the right is Charles James Fox, dressed as Falstaff. He is bearded and very fat, and wears a slashed doublet, hose, wide boots, a cloak, a ruff, and a high-crowned hat adorned with two feathers. Below, the title ‘Falstaff & His Prince’ is printed in capitals, and dialogue is printed in small italic letters to either side. The Prince says 'There is a Gentlewoman in this Town, her name is [blank],’ (the name is censored). Falstaff replies (quoting from The Merry Wives of Windsor): ‘Master George I will first make bold with your Money next give me your hand & last as I am a Gent[leman], you shall if you will Enjoy [blank’s] Wife.’](https://images.cogapp.com/iiif/sharc/Falstaff-Prince.tiff/full/622,/0/default.jpg)